By Gwendolyn D. Galsworth

As we read in this LMJ issue on lean turnarounds, lean is capable of changing the operational profile of nearly every work setting, and for the better. With their emphasis on the big four: cellular design; flow; standard work; and pull—these conversions can be rapid and life-saving.

However, the burning question is: when turnarounds are so rapid, can the culture be transformed as well? Yes, it has been known to happen. For most companies, however, is unlikely.

There are many available techniques for generating a cultural change: the formation of area teams; the kaizen blitz (aka, rapid improvement event); suggestion systems; and quality circles (or its updated counterpart). None, in my view, is more powerful or more valuable than the visual workplace in bringing about a complete transformation in work culture and an aligned, spirited, and engaged enterprise.

However, you and I may not be referring to the same “visual workplace”. Simply installing a bunch of visual devices, either copied from another facility or designed locally, to address some confusion or spot abnormalities is not the visual workplace I have in mind. That visual workplace rendition is limited both in scope and impact. The visuality I refer to is an equal and strategic partner to your lean conversion, a modality that brings with it a unique contribution—as powerful as lean and yet different. (note: the term “visual management” is not an equivalent but only a narrow part of the spectrum of visual function). Like the wings of a bird, both lean and visual are needed for a company to reach its destination of operational excellence. Yet they are separate.

Make no mistake: installing even a handful of visual solutions will have a positive impact on operations. Any time you share information by embedding it into a device, the chances increase that the right work will get done at the right time in the right way. The reason is simple: you do not have to search for the quality spec or guess at the quantity level. You do not have to double or triple check your work. You don’t even have to locate a binder or supervisor to get the information you need. Visual information sharing is always a positive, even if it has the limited scope of a series of point solutions.

To transform the culture of work, however, into one that supports operational excellence, you have to start from a different base, a different understanding. The correct understanding of workplace visuality is this: it is a language.

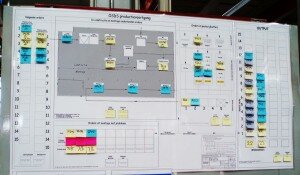

The vocabulary of the visual workplace language consists of the hundreds, often thousands, of visual devices invented by the workforce that uses them. As a language, visuality is both a means of individual expression and a vehicle for enterprise connectivity. Effectively implemented, the visual workplace has the potential to do this and more: it can impact the bottom line, many times with an increase of 15 to 30 per cent productivity. But to our point in this article, it is an equally mighty agent of culture change.

The process begins when we recognize and respond to the need to know. This need exists on every organisational level. In a visual workplace, we make that explicit and then use it as a lever. From operators to plant manager, every employee has a need to know. No one is exempt. The operative question is identical for each person in every enterprise function: what do I need to know that I don’t know right now in order to do my work?

Notice that “I” is the governing pronoun—not “we”. The language of visuality is rooted in the individual’s need for information vital for, but missing from, his or her work. I call this: the need-to-know. It is what makes the visual workplace an “I”-driven paradigm.

A fully-functioning visual workplace transforms the work culture because it is built on individuals, the individuals of the workforce—whether operator, plant manager, CEO, engineer or supervisor, everyone gets the information they need when and where they need it because of the visual devices they invent. Because these devices are pulled into place by the very people who need them, visuality automatically creates interested users. Ownership and adherence are built in. These devices are effective because, by design, they embed vital information into the living landscape of work—into the physical work environment itself. Information becomes coterminous with process.

Understanding this paradigm helps us appreciate why visuality cannot be enforced as a means for getting people to change their behaviors—or, by gum, their attitudes. A change in work culture cannot be imposed. It can only be “I”-driven.

The plant manager, for example, has a need-to-know wide array of contextual data, often many times a day. And they need to know it at-a-glance. Only then can they have the timely and accurate understanding of the current situation needed to assess the options and make decisions that move the organization forward.

Supervisors have an equally vital need-to-know within their locus of control—the department. When the answers they seek are embedded as visual devices, supervisors can do their job as logistical expediters smoothly and efficiently. Vital answers are available when and as needed. No more chasing down information. As a result, supervisors gain a small margin of breathing room in their work day; and their attention can naturally shift to a different and higher level of purpose. Supervisors can become leaders of improvement.

In a fully-implemented visual workplace, the cultural transformation deepens because the language of excellence has become the intentional foundation on which all work transactions are made. When logistical tasks of supervisors can be routinely addressed through embedded information sharing, they can reconceptualise their roles and themselves—because they have the margin to imagine both differently. Their identify shifts.

For operators, the need-to-know sounds like this: “I need to know where my tools are; I need to know which material to use for this order and what its heat treat level is; and, by the way, what’s the quality spec? I need those answers embedded into the living landscape of work because I don’t want to have to memorize them or find the binder where they are written—or find you, my supervisor, to ask.”

Listen closer and you will also hear this: “I want to be in charge of my corner of the world; and I cannot be unless I have information vital to the task at hand at my fingertips—accurate and complete because I have made it so. I am the re-designer of my work area and have made it my partner in work. And because I can rely on the things of the workplace to assist me in using them properly and safely, I can relax. I am in control. And I am free to let my mind imagine even more improvements. Or maybe even a true innovation to the process. Even though I don’t have a degree as an engineer, I can be a scientist of my own work. I can contribute. I can be a hero at work.”

In too many companies, the culture is out of control, with everyone struggling to get their own work done, isolated from others—struggling because the system is not working. Material is missing, specifications are missing, and information is missing. Everyone runs around looking for these. Or they simply stop and wait. They don’t trust the system; they don’t trust the company; they don’t trust you. They don’t trust themselves. They are on their own, entirely—and they know it.

No matter the employee or organisational level, people at work feel the pressure of not knowing and, with it, a looming fear of failure. The information is out there somewhere. But it needs to be here. Culture is behavior. And in this culture, people are either worried, hyper-vigilant or indifferent.

A visual workplace is radically and profoundly different. When the information is embedded in visual devices, it is where we need it and when—always. No hesitation. No struggle. People can do their work in harmony with others. They feel a sense of space—margin— within their own beings. They have room to breathe and to think. And that is transformative.

Because visuality is a language, the need-to-know pulls visual devices into place. When we can get information that is vital to our work at a glance, our behavior changes. We experience something unusual at work: control. Visuality gives us control over our corner of the world—and our attitude changes. And that’s a workforce that is spirited, engaged, and aligned with the corporate intent.

Visuality is the foundation for this sense of control over our corner of the world—our work. Something inside of us begins to relax. A small space opens. The pressure is off. We feel margin in our being. Margin to breathe, to think, to create.

This margin is the power that fuels your cultural transformation. Work makes sense because we have made it so. Visuality doesn’t just support an aligned work culture, it creates it.